How can principles of circularity be implemented into the procurement and use of notebook computers? How can you cut greenhouse gas emissions and save money at the same time? We’ve listened to experts in the field and analyzed the data. Here you’ll find practical, science-based advice on key considerations such as extending product life, energy efficiency, and why you should think twice before recycling.

Around 275 million notebook computers are produced and sold globally every year. Even though their manufacture requires a large amount of energy as well as a number of finite natural resources, their service life is often short. The typical IT contract is based on a three to four year use cycle. After that, many organizations face difficulties disposing of products, with many of them ending up as e-waste even though they are fully functioning. This way of handling IT products goes against the principles of the circular economy, where products should be kept in use for as long as possible, to save resources and retain value. The good news is the urge to implement more sustainable practices is growing. However, there are many choices to make during a notebook’s life cycle and it’s not always easy to know what’s best. We’ve looked into this issue to clarify what the most responsible way to manage notebook computers is. How can organizations reduce environmental impact and help promote a more circular life cycle?

Recycling — a less favorable solution in a circular economy

In theory, recycling may seem like a viable way to harvest precious metals and other materials from a notebook. But in reality, a very small amount of the assets included in our IT products are currently recovered in the recycling process. First of all, only around 20 percent of global e-waste actually reaches controlled recycling facilities. The rest may end up in landfill, is incinerated, or illegally exported to regions where e-waste legislation is weak or non-existent.

Even in those cases when a product reaches a controlled recycling facility, materials tend to lose value, or are lost altogether. There are several reasons for this. Notebooks contain a large number of materials and typically, recycling facilities cannot recover them all. Materials that are present in very small amounts are difficult and costly to extract. Rare earth metals and conflict minerals, such as tantalum, are often used in small quantities and are in many cases not recovered at all. Metals, such as gold, cobalt and palladium are only partially recovered during recycling and need to be extracted from the mines continuously to meet the demand. A material that often loses its value during the recycling process is plastic. The output is a downcycled, lower quality product. Plastics in notebooks may also contain harmful flame retardants and plasticizers that cause harmful health effects during recycling processes and make the materials unsuitable to use in new products.

Recycling methods are continually evolving, and in some leading-edge facilities, recycled materials are of higher quality, in some cases even similar to virgin materials. These higher end materials can be reused in the same type of product as they once came from, which meets one key aspect of realizing the circular economy. However, there are very few of these facilities, and bringing these solutions to scale will take time. For now, the focus must be on avoiding e-waste as much as possible.

Notebook design for a longer life

While extending the lifespan of notebook computers is necessary for reducing the climate impact of the IT sector, not all of them are designed for a long life. Circularity and product life considerations must be made up front — at the design and manufacturing stages. Today, too many products are disposed of because they break easily and are difficult to repair or upgrade.

The notebook computer is a mobile product, and it needs to be durable, withstand wear and tear as well as high and low temperatures. Vital components must be replaceable, so products should be possible to disassemble and spare parts need to be available. Battery quality is important too — products are often replaced because of poor battery performance.

Keynote: Circularity in practice

Criteria in TCO Certified enable circular solutions

In 2020, around 48 million notebooks certified according to TCO Certified, generation 8 were manufactured. These products are verified to meet a comprehensive set of sustainability criteria that are designed to promote a circular approach to the way IT products are manufactured and used. To enable a long lifespan, certified products must be durable and upgradeable as well as possible to repair and recycle. The notebook computers that meet the strict requirements of TCO Certified, generation 8 are well positioned for a long service life.

If all certified notebook computers that were manufactured in 2019 would be used for six years instead of four, it would result in a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions of approximately 6,230,400,000 kg carbon dioxide equivalents. This equates to the annual average carbon footprint of 1,391,000 people.

Conclusion 1

Extending product life cuts greenhouse gas emissions

Conclusion 2

Emissions lower when notebooks are upgraded instead of replaced

Conclusion 3

Buying new doesn’t compensate for emissions from manufacturing

Conclusion 4

Circular solutions are better also from a financial perspective

This is an updated version of an article originally published in our report Impacts and Insights: Circular IT Management in Practice.

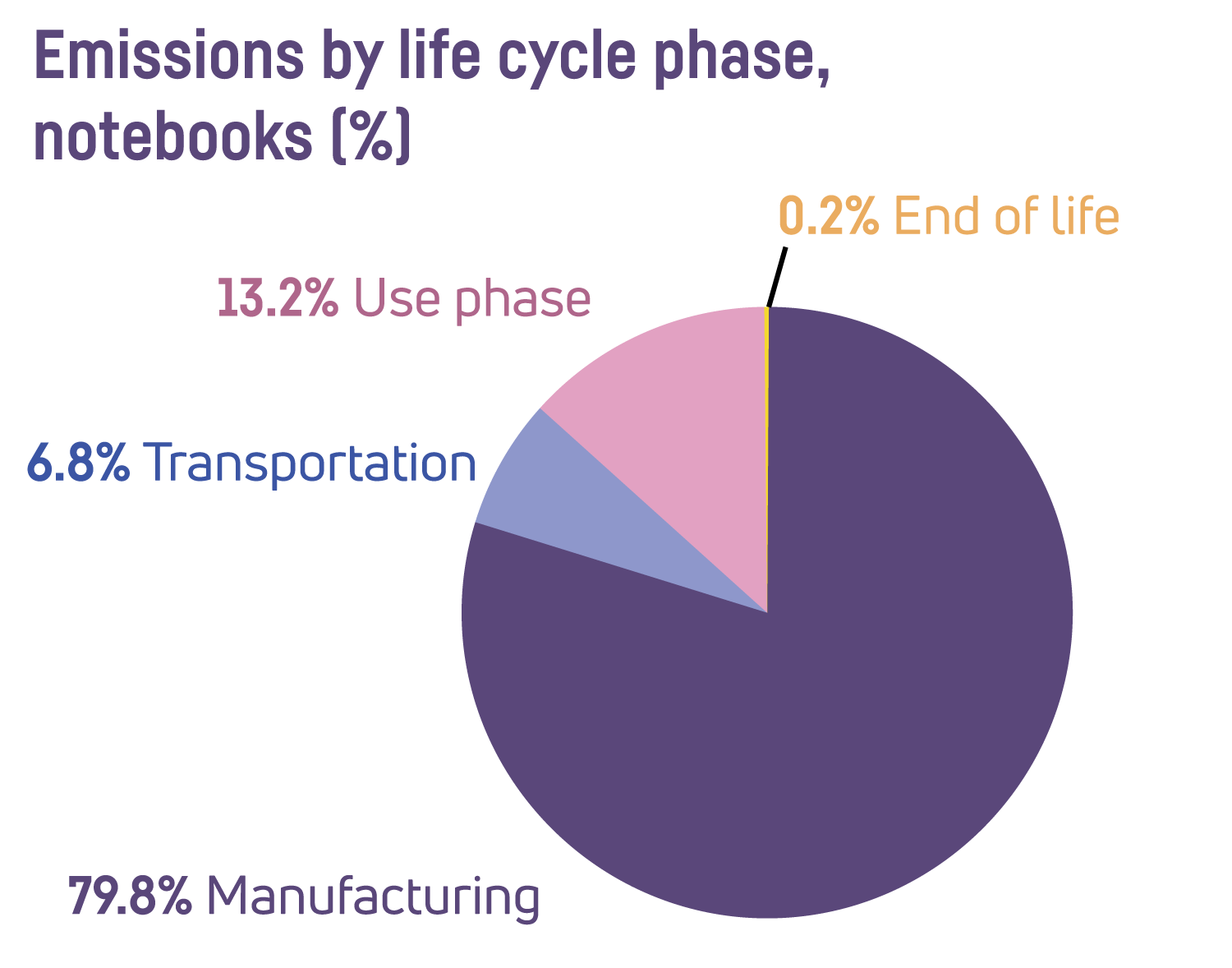

To identify the best way of lowering greenhouse gas emissions, it’s important to know how and when these emissions are produced. We looked at 15 carbon footprint reports for 14 inch business grade notebook computers from Dell, Lenovo and HP, commonly in commercial use worldwide, and interviewed Siddharth Prakash, senior researcher at the Oeko-Institut in Germany, specializing in policies and instruments for sustainable consumption and production. We investigated the greenhouse gas output from manufacturing, distribution, use and disposal, and how purchasing new, more energy efficient notebooks impacts greenhouse gas emissions, compared with extending the life of an existing device. Combining all these sources of information, our analysis concludes that a vast majority of the greenhouse gases are emitted in the manufacturing phase. Looking at a scenario where a notebook is used for four years, the total carbon footprint is 299 kg during its life cycle. Of this, 79.8 percent of the greenhouse gases are emitted in the manufacturing phase, 6.8 percent during transportation, 13.2 percent in the use phase, and 0.2 percent at end of life.

To identify the best way of lowering greenhouse gas emissions, it’s important to know how and when these emissions are produced. We looked at 15 carbon footprint reports for 14 inch business grade notebook computers from Dell, Lenovo and HP, commonly in commercial use worldwide, and interviewed Siddharth Prakash, senior researcher at the Oeko-Institut in Germany, specializing in policies and instruments for sustainable consumption and production. We investigated the greenhouse gas output from manufacturing, distribution, use and disposal, and how purchasing new, more energy efficient notebooks impacts greenhouse gas emissions, compared with extending the life of an existing device. Combining all these sources of information, our analysis concludes that a vast majority of the greenhouse gases are emitted in the manufacturing phase. Looking at a scenario where a notebook is used for four years, the total carbon footprint is 299 kg during its life cycle. Of this, 79.8 percent of the greenhouse gases are emitted in the manufacturing phase, 6.8 percent during transportation, 13.2 percent in the use phase, and 0.2 percent at end of life. For most users who work with standard software programs, notebook computers may function well for at least six years without upgrades to hardware such as hard drives, memory or battery. Sometimes though, and especially for users who work with more performance-demanding software, upgrades to hardware are needed in order to extend the notebook’s life. How will this affect greenhouse gas emissions?

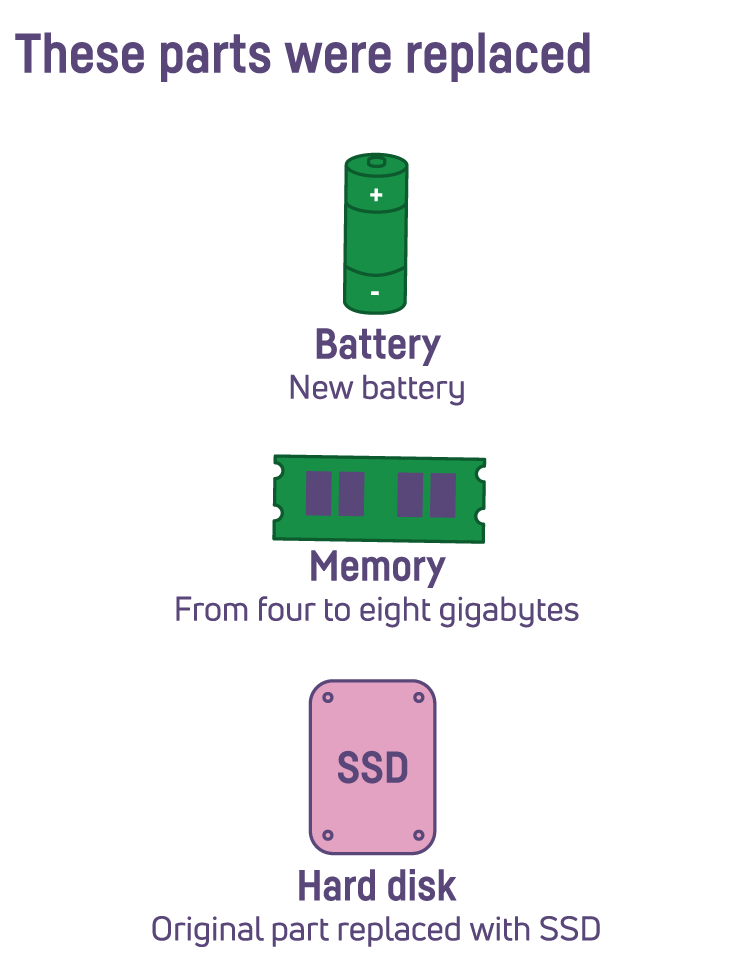

For most users who work with standard software programs, notebook computers may function well for at least six years without upgrades to hardware such as hard drives, memory or battery. Sometimes though, and especially for users who work with more performance-demanding software, upgrades to hardware are needed in order to extend the notebook’s life. How will this affect greenhouse gas emissions?

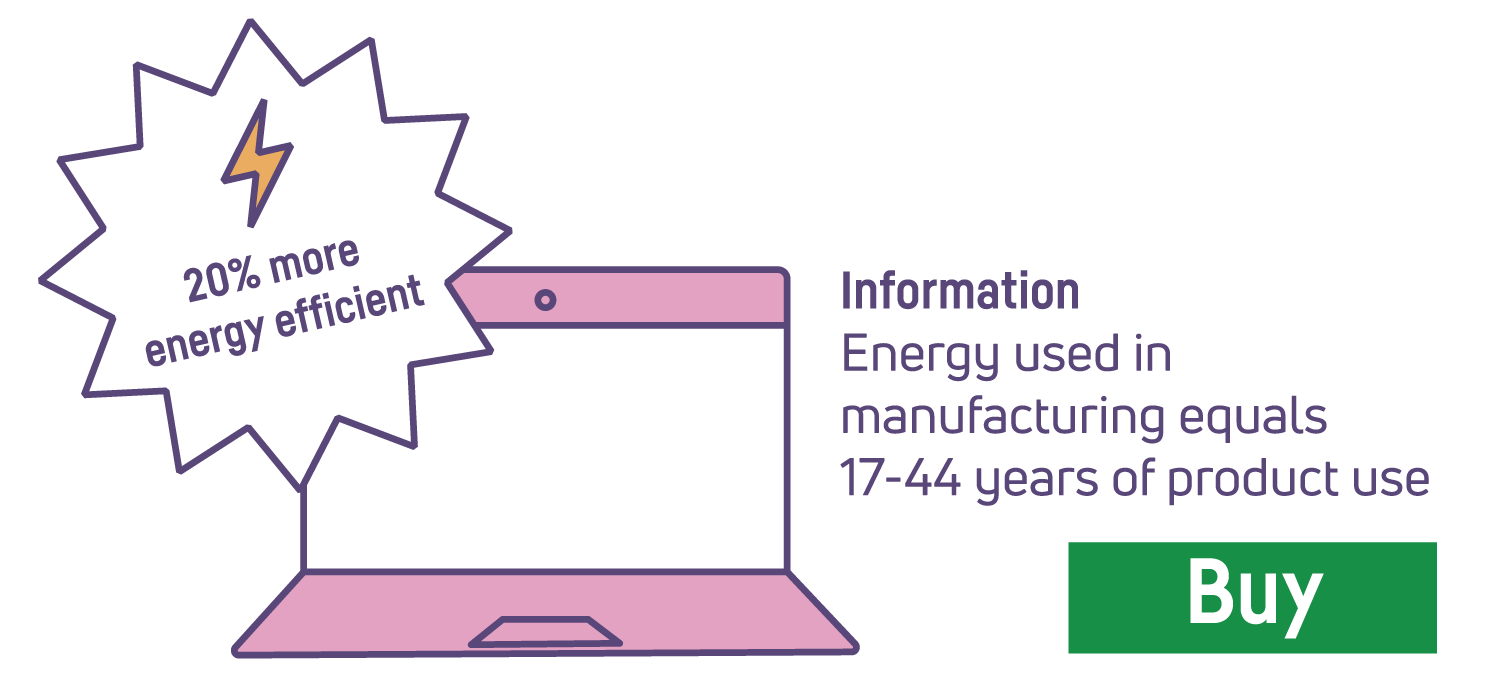

Many electronic products have become increasingly energy efficient, and in some cases, purchasing new equipment has actually been a way of lowering the environmental impact of the product during its life cycle. Is this also the case for notebook computers today?

Many electronic products have become increasingly energy efficient, and in some cases, purchasing new equipment has actually been a way of lowering the environmental impact of the product during its life cycle. Is this also the case for notebook computers today?

Purchasing new IT equipment in short contract cycles is expensive. It is often more costly than it needs to be, especially in the era of “best overall value” procurement, where factors like sustainability and life cycle cost are taken into account in procurement, alongside product price. Also, treating used IT products as waste instead of extending their life or even reselling them is a missed opportunity for cost savings and income. By extending lifetime from three to six years, the cost of purchasing and using a complete computer workstation can actually be reduced by 28 percent, or 527euro (570 US dollars), over a period of 10 years, even when the cost for upgrading 50 percent of the notebooks with new RAM, SSD and battery is factored in. Savings also include a reduced cost for purchasing the products, and for administering the procurement process when notebooks are purchased in longer intervals.

Purchasing new IT equipment in short contract cycles is expensive. It is often more costly than it needs to be, especially in the era of “best overall value” procurement, where factors like sustainability and life cycle cost are taken into account in procurement, alongside product price. Also, treating used IT products as waste instead of extending their life or even reselling them is a missed opportunity for cost savings and income. By extending lifetime from three to six years, the cost of purchasing and using a complete computer workstation can actually be reduced by 28 percent, or 527euro (570 US dollars), over a period of 10 years, even when the cost for upgrading 50 percent of the notebooks with new RAM, SSD and battery is factored in. Savings also include a reduced cost for purchasing the products, and for administering the procurement process when notebooks are purchased in longer intervals.